Listen thoughtfully, carefully, mindfully…then do something

Success is not the result of spontaneous combustion. You must first set yourself on fire.

—Reggie Leach

This idea was a kick in the pants. Lately I feel like I’ve been inundated with admonitions to listen carefully, deeply, mindfully…Pick your guru and each will say, start with listening.

- Stephen Covey: “Pass the torch and listen.”

- Susan Scott: “Waiting to talk is not listening.”

- Keith Ferrazzi: “When you ask someone’s opinion, your next job is to listen and give a damn.”

- Marshall Goldsmith: “Let go of ‘yes, but…’ – stop adding too much value and listen.”

- Warren Bennis: “Ask a probing question and then listen.”

- David Whyte: “The conversation IS the relationship.”

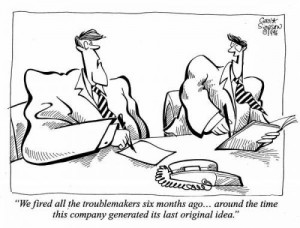

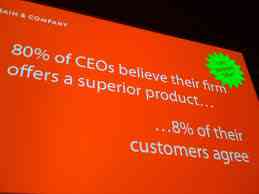

We had a conversation last week with Jennifer Kahnweiler, an expert on developing introverted people into powerful (and quiet) leaders. She has a segment in her book in which she addresses the downside of always listening. As she points out, when you are engaged in deep listening, by definition, you aren’t sharing information and knowledge, and you aren’t doing anything. When, of course, it’s the doing that translates into shared value and innovation.

Certainly in a state engaged listening, you are developing a heightened sense of situational understanding and honing your emotional fluency. Yet, if you are constantly operating in a listening mode – mindful or not, Jennifer points out a few pitfalls in her new book, Quiet Influence:

Loss of credibility: If you are constantly listening and not contributing, your colleagues and peers might begin to believe you have nothing to offer or contribute to the discussion.

Conflict avoidance: While engaged in mindful listening, you’ll certainly develop a stronger emotional fluency of your collaborators and can begin to sense divergent ideas, or conflicting mindsets on the team. If you don’t speak up to point these out, you’re losing a valuable opportunity to resolve potential conflicts.

Unproductive conversations: Collaboration needs to be reciprocal. When you fail to contribute based on what you’ve learned while listening, the conversation stalls and becomes unproductive.

Unheard ideas: And of course, you’re going to miss 100% of the shots you don’t take. However ridiculous your idea may be, your collaborator – and the world – will never know your ideas if you don’t speak up.

Take a chance. Ask a question, express an opinion, build a prototype. Fail forward.

If you’ve ever heard

If you’ve ever heard  Wayne Rooney is widely regarded as an astonishing soccer player – one of the greatest playing the game today. Also mercurial, brooding, even thuggish at times. He was recently banned for a game for intentionally kicking Montenegro’s Miodrag Dzudovic. As a kid he played non-stop – in the streets, in the house, in the backyard. And when he couldn’t play, he dreamed of playing soccer.

Wayne Rooney is widely regarded as an astonishing soccer player – one of the greatest playing the game today. Also mercurial, brooding, even thuggish at times. He was recently banned for a game for intentionally kicking Montenegro’s Miodrag Dzudovic. As a kid he played non-stop – in the streets, in the house, in the backyard. And when he couldn’t play, he dreamed of playing soccer.

As a family we ski quite a bit in the winter. We’re about two hours from Sugarloaf Mountain in Maine and the kids love it. A couple years ago, I would regularly launch off a series of ski jumps in the terrain park. It’s exhilarating. Drop down to approach the ramp, race up to the lip of the jump and sail high to a smooth landing on the downhill other side. Fifteen feet? Twenty? I probably exaggerate but it feels really far. If you get the speed right it’s smooth, easy and fun. I could do it all day. What a blast.

As a family we ski quite a bit in the winter. We’re about two hours from Sugarloaf Mountain in Maine and the kids love it. A couple years ago, I would regularly launch off a series of ski jumps in the terrain park. It’s exhilarating. Drop down to approach the ramp, race up to the lip of the jump and sail high to a smooth landing on the downhill other side. Fifteen feet? Twenty? I probably exaggerate but it feels really far. If you get the speed right it’s smooth, easy and fun. I could do it all day. What a blast.