The High Cost of Conformity

Imagine you are in a room with seven other people, and the person running the meeting presents everyone with two cards. On the left-hand card is a line. On the right-hand card are three lines of differing lengths. You are asked to pick which line on the right card matches the length of the line on the left card.

The answer is obvious. Any fool can see the right answer. But each person, in turn, around the table picks the wrong line, the wrong answer. Now it’s your turn. What do you do? Do you speak your mind? Speak the truth? It’s baffling that these people can’t see what you see so obviously. What’s wrong with these people?

About a third of us would agree with the group. Against our opinion, against what is so clearly obvious, we would reluctantly agree with everyone else’s wrong choice. These are the results of a series of psychology experiments conducted in the 1950s by Solomon Asch. In fact, in control groups during the experiment, over 98% of the participants recognized the correct answer, and yet 32% voted incorrectly along with the rest of the group.

When we perform tasks or engage in activities because “we’ve always done it that way” or because the person with the greatest seniority in the room suggested it, we’re acting out of conformity. Don’t misunderstand, conformity can be a great thing – it can allow teams to soar, military groups to function seamlessly and efficiently, and allow decisions to be made faster. Conformity is acting in accordance with social standards and conventions. I’m certainly glad we have accepted communication and behavioral conventions over at Air Traffic Control, and the people over at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. (Here’s the audio feed from ATC at my home airport in Portland, Maine. I’m certainly glad they’re not just making it up as they go.)

In fact, Charles Efferson and his colleagues demonstrated that social conformity can present a higher rate of correct decisions, and higher performance in specific tasks. Conformity is how we deal with the complexity of life, the tsunami of data and information we are presented with, the unmitigated firehose of media we are bombarded with. We look at what other people are paying attention to. What they are looking at, what they are doing. And we do that.

But positive and creative deviance is what drives change. On December 1, 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama, Rosa Parks, at age 42, refused to obey bus driver James Blake’s order that she give up her seat to make room for a white passenger. In her own words, she was “tired of giving in.”

Know that we are all vulnerable to conformity. Think of these small awarenesses when participating in a group decision:

- be aware of our vulnerability to conformity

- cultivate healthy skepticism towards our own group

- be willing to disappoint people

It’s the difference between belonging to a group, and simply fitting in. When we fit in, we conform. When we feel a strong sense of belonging, we feel enabled to be ourselves, wholly and authentically.

To learn about how build a culture of continuous learning see:

- Steve Shapiro on Out-Innovate the Competition

- Marilee Adams on Question Thinking: The Key to Transforming Mindsets

- ____________________________________________________

Twitter: @gshunter

Say hello: email@gshunter.com

Web: www.shawnhunter.com

A colleague called me yesterday and said, “I want to talk about commitment.” We had just finished brainstorming an idea over a few days and we both agreed we had something good, quite good, excellent actually. She wanted to have that conversation about accountability, about follow through. Which got me thinking about how to improve the odds of completing anything we set our minds to.

A colleague called me yesterday and said, “I want to talk about commitment.” We had just finished brainstorming an idea over a few days and we both agreed we had something good, quite good, excellent actually. She wanted to have that conversation about accountability, about follow through. Which got me thinking about how to improve the odds of completing anything we set our minds to.

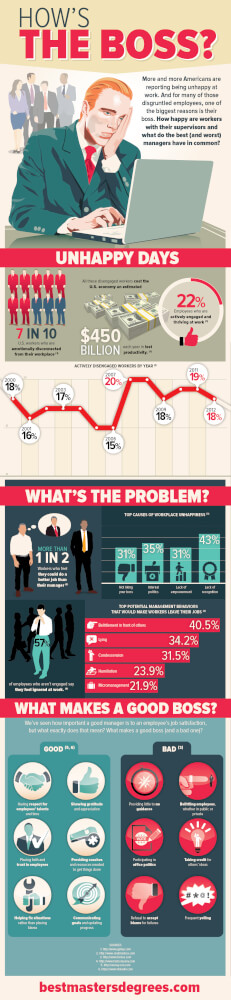

According to researcher Robert Hogan, 75% of working adults today say the most stressful, most dreaded interactions they have at work is with their immediate boss.

According to researcher Robert Hogan, 75% of working adults today say the most stressful, most dreaded interactions they have at work is with their immediate boss. Recently over here at

Recently over here at  Our company

Our company  Slydial

Slydial Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of