Why We Learn Faster When We Love It

I have never set a single word down on paper with the thought of being paid for it … I have written because it fulfilled me.”

– Stephen King

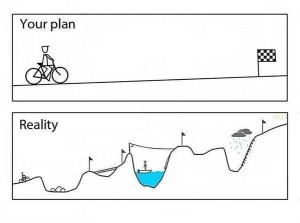

Practice doesn’t make perfect. There is no perfect. Great practice will hone the good habits, and get rid of the bad habits. Poor practice is practicing your mistakes over and over until they’re ingrained.

By now, most of us have read, or heard of, the 10,000-hour rule, in which 10,000 hours is the magic practice barrier after which we get to be experts and gurus. Unfortunately that has been a misrepresentation of the work of K. Anders Ericsson, and his colleagues from Florida State University from the 1990s. Ericsson never claimed 10,000 hours was the magic expert barrier.

However, research does support the idea of reinforcing “time on task.” In sports, most believe today the best coaching and training involves increasing the amount of “touches on the ball” instead of an older style of coaching in which players stand around watching a demonstration and then take individual turns doing one activity. A poor practice looks like kids standing in lines. A good practice has everyone involved.

We learn by watching, but we learn faster by doing.

Very recent research examined 88 different studies on the effects of practice over time and concluded that practice does count, but much less than previously argued by Malcolm Gladwell and others. Practice certainly matters, but other factors were equally important such as the age in which the activity was introduced, and how much the participant enjoyed the activity. In one example, children reported thirty times higher reading comprehension when they also reported enjoying the reading.

A successful person continues to look for work after he has found a job.

That may come as no surprise, but keep that in mind when making project and task assignments in your professional work. Yes, if you make task invitations that are a stretch but that people might enjoy, that’s an invitation for excellence. But when you offer project and task invitations for activities people detest, you are far more likely to get mediocre results. And research seems to suggest that no amount of arguing for pluck, grit and perseverance, will improve results when the task presented is against their skill set.

In an interview with Scott Turicchi, CFO of J2, a 500M dollar technology company, he said he very intentionally moves team players to different positions within his organization so they have the benefit of seeing different sides of projects and understand the greater picture of any particular project or deal in the works.

As Scott described, there’s an even more important reason to working in different roles, other than job experience and perspective. The most valuable reason is to find what you love, to find the intersection of what you are good at, and what you love to do. Scott said that the kinds of people he likes to hire are those who have passion for their work.

And how are you going to find your passion if you don’t try something new?

Your beliefs don’t make you a decent person, your actions do.

– Maya Angelou

- Join my Email updates for regular updates on leadership and life

- Learn more about my Speaking work

- ____________________________________________________

Twitter: @gshunter

Say hello: email@gshunter.com

Web: www.shawnhunter.com

Our company

Our company  From the kitchen window Christopher could see his wife was getting frustrated. Over and over again, Dana was running awkwardly, hunched over, down the driveway while holding on to the back to Will’s bicycle. At the time, six year old Will was still terrified of riding without his training wheels, or without his Mom holding him up. Christopher watched as his wife and son repeated the same failed routine again.

From the kitchen window Christopher could see his wife was getting frustrated. Over and over again, Dana was running awkwardly, hunched over, down the driveway while holding on to the back to Will’s bicycle. At the time, six year old Will was still terrified of riding without his training wheels, or without his Mom holding him up. Christopher watched as his wife and son repeated the same failed routine again.

They were unbeatable, invincible. The supergroup, the dream team.

They were unbeatable, invincible. The supergroup, the dream team.  I thought he was kidding. Until I watched him do it right in front of me. He didn’t do it fast and flashy like a televised spectacle, but he solved the Rubik’s Cube before my eyes in a few minutes. I was impressed, but not in the kind of way that I felt inspired to try it myself. Just impressed.

I thought he was kidding. Until I watched him do it right in front of me. He didn’t do it fast and flashy like a televised spectacle, but he solved the Rubik’s Cube before my eyes in a few minutes. I was impressed, but not in the kind of way that I felt inspired to try it myself. Just impressed. Sometimes Charlie, who is two years older than Will, comes and helps out at our U11 soccer practice, just as he did this evening. Eleven year old son Will often finds his brother’s presence annoying and intrusive at his practice, but the other kids really like it.

Sometimes Charlie, who is two years older than Will, comes and helps out at our U11 soccer practice, just as he did this evening. Eleven year old son Will often finds his brother’s presence annoying and intrusive at his practice, but the other kids really like it.