Labels, mazes and stupefying change

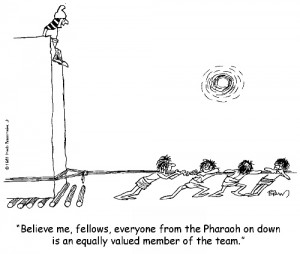

Last week I sat in and listened to an interview as she spoke with my collague Taavo about what it means to be a leader. She kept returning to a few key phrases throughout the conversation. One expression she repeated consistently was “Ban the heirarchy.”

That expression kept jumping into my mind as I read through a study on the relationship between giving heirarchical labels to individuals and its negative impact on their ability to solve complex puzzles. No one I talk to seems to disagree with the fact that as we live in a world of stupefying change, the ability to digest complicated information and then transform it into meaningful ideas or innovation is critically valuable. And yet, we often persist in such debilitating labels.

In the study called Names Can Hurt You, a group of researchers from the World Bank went to rural India and conducted a series of problem-solving tests with 6th and 7th grade students from both the highest and lowest castes. Before the test began, each student was privately interviewed and asked their name, caste, father’s name, grandfather’s name and village. Then they were divided into three groups. Each group was first asked to solve mazes on their own. And then the researchers created a competitive tournament game in which the students were incentivized to perform better. The best performers gained peer recognition and cash.

The first group, known as Caste Concealed, consisted of 3 high caste students (H) and 3 low caste students (L). Because the students were selected from multiple villages, and because none of their personal information was shared with other students, a child might reasonably assume the others are unaware of their caste. As expected, in this group all 6 students performed comparably well on the puzzles, and responded positively to the social and monetary incentives introduced in the competitive tournament game.

The second group, know as Caste Revealed, again consisted of 3H and 3L students. However, at the beginning of the session the researchers read aloud each child’s background information, revealing their identity and caste. In this group all students did not improve or respond to incentives in the tournament portion of the test.

The third group, Caste Segregated, consisted of 6H and 6L students, and again all identities were revealed prior to starting the session. In this group, not only did the students remain unresponsive to competitive incentives, it had a negative impact on the lower caste students. Once their identity was revealed in a larger group they performed even worse when incentivized to do better.

Huh! Imagine that: in team-based problem-solving environments, when certain members of the group are labeled as inferior, they perform worse on complex problems.

Avoid labels, speak in terms of “we.” And in the language of world-class innovative – and non-heirarchical – company W.L. Gore, “No one may commit another.” That is to say, you may invite or challenge people to take on tasks and accountability but you may not commit another person to doing something. In their culture, people have influence based on the compelling power of their ideas and leadership ability to get things done, not based on their title.

Recently Annie (then 6, now 7) and I were at the store picking out a card to for her to send to a friend. In the card display was a big section dedicated to Taylor Swift. We examined each card – Taylor Swift looking dreamy, sassy, alluring, or even defiant. Taylor can certainly strike a pose. I asked Annie to pick one.

Recently Annie (then 6, now 7) and I were at the store picking out a card to for her to send to a friend. In the card display was a big section dedicated to Taylor Swift. We examined each card – Taylor Swift looking dreamy, sassy, alluring, or even defiant. Taylor can certainly strike a pose. I asked Annie to pick one. In October of 2003 in Atlanta at a global company meeting, as the new CEO of Schering-Plough, Fred Hassan stood on stage before thousands of sales professionals from around the world and said:

In October of 2003 in Atlanta at a global company meeting, as the new CEO of Schering-Plough, Fred Hassan stood on stage before thousands of sales professionals from around the world and said: Our twelve year old son walked into the lunchroom at Sugarloaf ski resort a couple weeks ago and said quietly, “I learned how to do a 360.”

Our twelve year old son walked into the lunchroom at Sugarloaf ski resort a couple weeks ago and said quietly, “I learned how to do a 360.”