Turkeys, Flash Freezing and Cafeteria Trays

Gerry Thomas, a sales executive at Swanson, had been flying around the country and had just seen what Pan American airlines was doing with compartmentalized in-flight food offerings. He and the executive team at Swanson coupled this notion with Clarence Birdseye’s new flash freezing technique, and then added the catchy product label “TV Dinner” that fit beautifully with the cultural explosion of television. Their great market opportunity was the eight million moms who were joining the workforce after WWII, who were also enjoying an abundance of electrical home appliances like ovens, refrigerators, freezers, and of course televisions.

Turkey Glut Crisis + New Technology + Market Inflection = Bonanza of Realized Value

Swanson thought they might sell five thousand units the first year. They sold ten million at .98 cents each. Big hit, and now you understand how the intersection of technology, inspiration, marketing and resources made it happen. But does that formula work again today? Here’s the difference now:

Resources are scare, not abundant: From water to textiles to lumber, the availability and premium placed on the natural resources we use to create the consumer products and comestibles are in high demand and, in the case of fossil fuels and water particularly, are increasingly precious.

Talent is global, not local: Historically if you had a local workforce that was obedient, diligent, and brought expertise and skill to bear executing on top-driven strategies, you had competitive advantage. The future is most certainly now in terms of the ability to connect need with a globally-dispersed labor force – highly talented, motivated, and comparatively cheap by U.S. standards. And all connected by the cost of the internet, $0.

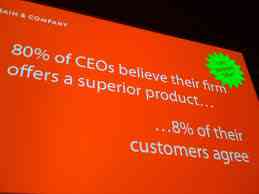

Innovation is democratized, not top-driven: No longer can firms rely on the the wisdom of a handful of insightful strategists at the top of a pyramid, when meanwhile companies like Rabobank or Best Buy are doing a better job of catering to customer need by creating mechanisms to actively listen to, and incorporate the interests of customers, and know-how of line personnel.

Never let a good crisis go to waste.

Think big! Blue sky! Anything is possible! Let’s build the next iPhone. Or better, let’s disrupt our own business model with a seismic market change, like iTunes. No…wait, like Spotify!

Think big! Blue sky! Anything is possible! Let’s build the next iPhone. Or better, let’s disrupt our own business model with a seismic market change, like iTunes. No…wait, like Spotify! I was listening to a podcast yesterday of Adam Grant talking about his new book

I was listening to a podcast yesterday of Adam Grant talking about his new book  If you’ve ever heard

If you’ve ever heard  Wayne Rooney is widely regarded as an astonishing soccer player – one of the greatest playing the game today. Also mercurial, brooding, even thuggish at times. He was recently banned for a game for intentionally kicking Montenegro’s Miodrag Dzudovic. As a kid he played non-stop – in the streets, in the house, in the backyard. And when he couldn’t play, he dreamed of playing soccer.

Wayne Rooney is widely regarded as an astonishing soccer player – one of the greatest playing the game today. Also mercurial, brooding, even thuggish at times. He was recently banned for a game for intentionally kicking Montenegro’s Miodrag Dzudovic. As a kid he played non-stop – in the streets, in the house, in the backyard. And when he couldn’t play, he dreamed of playing soccer.

In October of 2003 in Atlanta at a global company meeting, as the new CEO of Schering-Plough, Fred Hassan stood on stage before thousands of sales professionals from around the world and said:

In October of 2003 in Atlanta at a global company meeting, as the new CEO of Schering-Plough, Fred Hassan stood on stage before thousands of sales professionals from around the world and said: True story: a couple of years ago a friend came over to visit and chat about some business ideas. My daughter was napping upstairs, my wife was out running, and the two of us were sitting in lawn chairs in the backyard watching our two boys (6 and 8 at the time) try to “drop in” on a skateboard into the half pipe ramp we had built together.

True story: a couple of years ago a friend came over to visit and chat about some business ideas. My daughter was napping upstairs, my wife was out running, and the two of us were sitting in lawn chairs in the backyard watching our two boys (6 and 8 at the time) try to “drop in” on a skateboard into the half pipe ramp we had built together. The Mayan weren’t the only ones to predict the end of the world. Or rather I should say, those who interpreted the Mayan to have predicted the end of the world aren’t the only ones who have predicted the end of the world.

The Mayan weren’t the only ones to predict the end of the world. Or rather I should say, those who interpreted the Mayan to have predicted the end of the world aren’t the only ones who have predicted the end of the world.