When to Let Others Fail on Their Own

It was getting out of hand. It was time for an intervention. Only a year earlier we had a 30 minute “screen time” media option in our house for our three kids. After homework, after chores, after mealtime together, and after checking in and sharing with us their daily activities, they could zone out on NetFlix, Instagram, TV, or whatever they wanted for 30 minutes. In fact, this turned out to be a rather enjoyable time for us as well. While kids blanked out on devices we could chat in the kitchen cleaning up after dinner.

A year later it had devolved into our kids leaping into one, then two-hour headphone-wearing journeys silently watching Parks and Rec, or lost in Taylor Swift albums, or bingeing on FIFA Soccer on XBox. All drifting quietly alone in corners of the house.

I’m all for music and movies, and sometimes throw dance parties with the kids in the living room, or have sessions of watching Forrest Gump, laughing together. But this had gotten out of hand. The rules had lost meaningful consequences, and often we were too exhausted to martial our efforts to stop it. It was time to break the habit.

It hasn’t been consistently effective, but instead of insisting, demanding or confiscating their devices, we have had some progress when we initiate playing with our kids like building a ski jump or playing soccer in the back yard, or assigning small jobs like setting the table or preparing parts of dinner, or simply explaining that staring at a screen near bedtime makes it hard to go to sleep. And when all else fails I quietly go into the basement and unplug the wifi router.

So how do we instill better decision-making in our kids? There are a few clues in recent studies from Brigham Young University in which researchers followed 325 families over a period of four years, examining the behavior of the families with kids between the ages of 11 and 14. After examining parenting styles, family attitudes and subsequent goals attained by the kids, the researchers concluded that three key ingredients consistently created higher levels of persistence, confidence, and higher performance in school as well:

- a supportive and loving environment

- a high degree of autonomy in decision-making

- a high degree of accountability for outcomes

In other words, ensure that there is high trust and unconditional love and support. Then let them make their own choices in recognition of shared understanding of consequences. Believe me, this certainly doesn’t always work. In our experience, a 14-year old does not always make thoughtful and conscientous decisions when granted autonomy. That’s the understatement of the week, but it is the eventual goal because in a few short years he will be making many of these decisions without us around.

I had an interview recently with the CEO of a 6 billion dollar company and he told me that sometimes he knows a project or initiative of a junior team will fail. He has the experience and the insight to recognize that it’s likely to bomb. But he lets it unfold anyway. He believes that as long as it’s not a mission-critical failure, it’s more important to let people go through that learning experience themselves. They need to have the experience of understanding first-hand that a particular process or initiative won’t work.

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

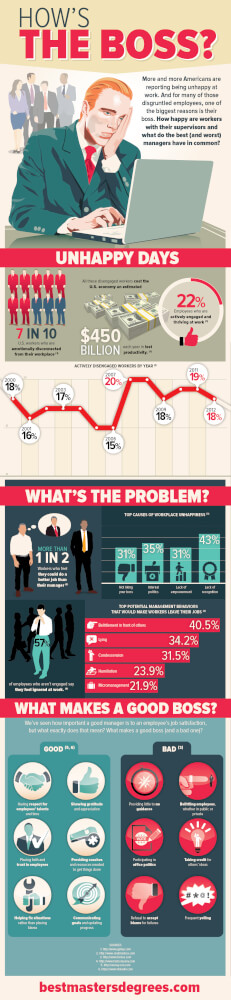

According to researcher Robert Hogan, 75% of working adults today say the most stressful, most dreaded interactions they have at work is with their immediate boss.

According to researcher Robert Hogan, 75% of working adults today say the most stressful, most dreaded interactions they have at work is with their immediate boss. Slydial

Slydial Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of  Our company

Our company