Stop Being Afraid of Getting Fired

Yes, you could lose your job for being inept, incompetent, missing deadlines and milestones, or simply failing to do the work. But you will not be fired for taking chances, and embracing risk and then accepting the responsibility that goes along with it. And if you are fired for taking an honest chance, with positive intention, and then owning the outcome, your boss is a coward, and your company is on the brink of irrelevance.

So most of us don’t take chances at work. Instead we take crap from management, accept workplace bullying, go along with idiotic ideas, follow unethical orders, hide our opinions, and mask our true identities. We even accept lower salaries. All because we fear losing our job, or because we are trying desperately to fit in.

Fifty years ago only experts worried about cigarettes, drunk driving, and wearing seat belts. The rest of the general public was more alarmed about nuclear attacks, Russian invasions, and asteroid impacts.

Today you are more likely to be struck by lightning (1 in 960,000) than you are of being killed in a terrorist attack (1 in 20 million). You are far more likely to be killed by your own furniture, or drown in your bathtub, than from a terrorist attack. And you are 200 times more likely to die in a car accident than a plane crash. We fear the wrong things.

Risk equals probability multiplied by consequence. In other words, smoking cigarettes or driving while texting is waaay more risky than worrying that you are going to be kidnapped and held for ransom. But risk is different than fear. Risk is quantifiable, it’s something you can calculate, while fear is perception.

The difference between risk and fear is, of course, control. When you are smoking or driving a car you are in control. When you imagine being attacked by a bear on vacation in Yellowstone Park (1 in 2.1 million), you have no control whatsoever. It’s a terrifying thought. It could stop you from taking a nice walk in the woods.

After September 11, 2001, 1.4 million people changed their travel plans to avoid flying, choosing to drive instead. Driving is far more dangerous. The decision to drive, instead of fly, caused an estimated 1,000 additional auto fatalities.

There’s a number of other criteria that also affect our perception of risk. Timing is a big one. When we believe that the risk is imminent, we perceive it as more dangerous, and longer term risks are viewed as more moderate. This explains why we postpone exercising and order another glass of wine. There’s no immediate risk, right? But habits build, and pretty soon the couch potato routine turns into very real health disabilities.

Familiarity is also one of our biggest barriers to attempting anything challenging and difficult. When we are familiar with the challenge, we view it as less risky. Yet statistically safe activities, which we have never done before, are viewed as terrifying.

Just last night our family watched a show about big, scary waterslides around the world. Waterslides are among the safest, and most controlled recreational environments, complete with professionals who are monitoring the entire experience. But as we saw in the TV show, time after time, people would balk at the last minute and refuse to participate in the waterslide.

Another consideration that halts our ability to accept risk is considering how reversible the consequences are. Losing your job is an irreversible experience, therefore we view the risk as higher.

All of these factors – familiarity, control, reversibility, and timing – contribute to our sense of risk and fear. However, here is one thing we know to be true. Great leadership, remarkable innovations, and outstanding service, begin with initiative, and embracing risk and the accountability that comes with it.

Initiative and conscientious risk-taking are the hallmarks of great team members and great companies. Yet, this learned behavior only happens when people feel psychologically safe at work. If you work in the kind of company that respects the psychological safety of teams, you are more likely to speak up, share ideas, ask for help, and take initiatives.

If you are a leader responsible for a team, you likely have deadlines and objectives for your team to accomplish. The best way to get team members to step up is to make them feel psychologically safe to take chances.

To learn more about adopting a learning mindset and driving innovation see:

- Steve Shapiro on Out-Innovate the Competition

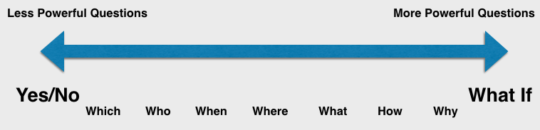

- Marilee Adams on Question Thinking: The Key to Transforming Mindsets

- ____________________________________________________

Twitter: @gshunter

Web: www.shawnhunter.com

Our company

Our company  Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of  Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of  Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of