Yes, You Will Succeed: Three Keys to Building Persistence.

“Amateurs sit and wait for inspiration. The rest of us just get up and go to work.”

– Stephen King

Back in the early 90s we used to go to a club in Charlottesville VA to see Dave Matthews and his band play. It was free to get in. One time we drove there and the doorman asked for $5, and we were like, “What!? What a ripoff, it’s just Dave.” During that same time period, I found myself president of the Student Activities Union at my college in North Carolina, a job which mostly required throwing parties and sometimes managing intramural leagues. I discovered if your job is to throw parties, people often recommend bands to you. A friend recommended some band from Columbia SC I had never heard of, but he assured me they would rock the house. So I called up Darius Rucker and asked if his Hootie and The Blowfish band would come play at our school. He asked for a keg of beer to play.

It seems like I blinked, but once I picked my head up to pay attention to popular music a couple years later, Dave Matthews and that Hootie band were playing stadiums at $200 a seat, and touring the world.

But here’s the thing: All of those blockbuster songs like Ants Marching, One Sweet World, Only Wanna Be With You, Hold My Hand, and so on, they were playing those same songs in little bar clubs for fourteen people back in the day. And had been playing them for years. They didn’t get famous and then write hit songs. They wrote hit songs and the world didn’t know it, until after they had played and played them again and again.

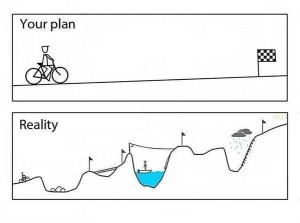

This is the myth of “suddenly” becoming famous. We don’t become successful overnight. We become successful as a result of showing up every day and putting in the hours, developing deep expertise and finding our tribe over time. Or as Aristotle so wisely put it, “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, therefore, is not an act but a habit.”

The standout word of the day is Grit. We implore our kids to persevere, to stay in the game, to try new ways of solving a problem. We encourage our colleagues to “fail faster” in expectation of finally arriving at an innovative breakthrough. We all just need to be a bit more gritty. One parent in California has a Kickstarter campaign to develop a line of dolls action figures for boys called Generation Grit.

But how do we instill a sense of stick-to-itiveness in our kids, and our colleagues? There are a few clues in recent studies from Brigham Young University in which researchers followed 325 families over a period of four years, examining the behavior of the families with kids between the ages of 11 and 14. After examining parenting styles, family attitudes and subsequent goals attained by the kids, the researchers concluded that three key ingredients consistently created higher levels of persistence:

- supportive and loving environment

- high degree of autonomy in decision-making

- high degree of accountability for outcomes

There it is again – that word autonomy. From previous research by Teresa Amabile and others, we have known for some time that high levels of autonomy lead to more creative outcomes. But here we also see that high levels of autonomy also build greater persistence.

According to Paul Miller, associate professor of psychology at Arizona State University, “When held accountable in a supportive way, mistakes do not become a mark against their self-esteem, but a source for learning what to do differently. Consequently, children are less afraid of making mistakes, are more inclined to try to make better choices in order to demonstrate that they can accomplish and live up to the expectations they share with their parent(s).”

It’s not a glorious job. And would likely be completely forgettable, if not for the frantic brushing down the ice. It’s distracting until you figure out that they are actually making the stone go faster by polishing the ice in front of the sliding stone. Sometimes I wonder if they accidentally bump into the other stones on the ice. I’ve never seen it happen. But it’s the role of the sweeper that can often make the biggest difference in the outcome in a game of curling.

It’s not a glorious job. And would likely be completely forgettable, if not for the frantic brushing down the ice. It’s distracting until you figure out that they are actually making the stone go faster by polishing the ice in front of the sliding stone. Sometimes I wonder if they accidentally bump into the other stones on the ice. I’ve never seen it happen. But it’s the role of the sweeper that can often make the biggest difference in the outcome in a game of curling. Colgate once introduced a line of dinner entrees. Harley-Davidson rolled out their own perfume. The

Colgate once introduced a line of dinner entrees. Harley-Davidson rolled out their own perfume. The

They were unbeatable, invincible. The supergroup, the dream team.

They were unbeatable, invincible. The supergroup, the dream team.

What’s your most enjoyable pop music out there today? Mumford & Sons? The Lumineers? Carly Rae Jepsen?

What’s your most enjoyable pop music out there today? Mumford & Sons? The Lumineers? Carly Rae Jepsen?  In 1968 Dick Fosbury astonished the world at the Mexico City Olympic Games by clearing 7′ 4″ 1/4 inches in the high jump. His efforts before 80,000 people were an aberration – an anomaly in track and field events. Dick was a gangly 6’3″ athlete who hadn’t excelled at any event in track and field at his Medford, OR high school and he unveiled a maneuver to set a world record. More remarkably, his competitors failed to recognize and adopt his innovative style and lost – not only on that occasion, but for years to come because they couldn’t acknowledge the power of his innovation.

In 1968 Dick Fosbury astonished the world at the Mexico City Olympic Games by clearing 7′ 4″ 1/4 inches in the high jump. His efforts before 80,000 people were an aberration – an anomaly in track and field events. Dick was a gangly 6’3″ athlete who hadn’t excelled at any event in track and field at his Medford, OR high school and he unveiled a maneuver to set a world record. More remarkably, his competitors failed to recognize and adopt his innovative style and lost – not only on that occasion, but for years to come because they couldn’t acknowledge the power of his innovation.