Relentlessly Positive, Personal and Specific

Before the game I approached the other coach. Usually we share a few friendly words with the visiting coaches, but I wanted him to understand what he was up against.

So after we exchanged handshakes and said hello, I pulled him aside out of earshot of our teams and said, “Look, I just want you to know we’ve lost every single game this season. We’ve been getting crushed actually. I don’t think the boys are frustrated, and we certainly focus on teamwork, hard work and fair play, but honestly we’ve been getting killed. By everyone. I just thought you should know. So maybe if it looks you’re having a runaway win, please keep that in mind.”

He looked at me and said, “We have too! We’ve lost every game!” Perfect. And so with that understanding between us coaches we opened up another U11 boys soccer game on a beautiful Saturday.

And sure enough, the game was fair and competitive. From the opening whistle both teams had their share of small frustrations and grand triumphs. There was more generous passing, more vocal encouragement between the players, and less complaining about positions. In fact, several players were asking – nearly begging – to play defense. It was a glorious moment of camaraderie.

Early in the second half, we found ourselves in the strange, and foreign, position of leading by one goal. Coach Scott and I agreed we were quietly cheering for the other team to score. And wonderfully, they did score to tie it up. In the end, we astonished ourselves and won the game. Afterwards, the moment of both teams slapping hands and congratulating each other felt honest and earnest. I heard very few complaints about either the referee or opposing players.

I’ve participated in a number of coaching clinics, and read quite a bit of material on youth coaching, and developing talent. Curiously, there remains a fairly large minority of parent volunteer coaches nationally who have the perception that learning constructive coaching techniques from experts, and attending coaching certification and counseling is unnecessary and without value.

And yet, these same studies reflect that once coaches adopt “relentlessly positive” approaches to both skill development on the field and social development with their teammates, some pretty remarkable things happen. To begin with, while up to 26% of kids nationally quit sports, only 5% of kids quit the game when they have a coach trained in Coaching Effectiveness Training (CET). Not only that, those children who started the season with lower self-esteem and played for a “relentlessly positive” coach showed a greater increase in self-esteem over the season.

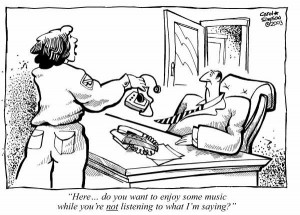

I had an interview last week in New York with child psychologist Joel Haber who affirmed these methods and reminded that positive coaching still needs to be personal and specific, not just positive. Saying “great job!” isn’t nearly as effective as say something specific such as, “I like the way you always stayed in front of the attacker when defending. You stayed in front of him and pushed the ball to the outside. He never had a chance to get by you. That worked great.”

Joel also reminded me of the downside of negative coaching. When a child leaves the field during a game and you point out something they did wrong, it leaves a powerful emotional wake. It not only conveys the message that you were disappointed, it won’t increase their learning and performance later either. When they go back on the field, their head will be filled with what not to do, instead of what to do. It has a paralyzing effect.

Aside from a smattering of applause here and there, the parents were completely silent. And myself, as the coach, instead of standing on the sidelines and giving instruction periodically to players, I was sitting on the bench watching quietly, with a clipboard updating positions where the kids were playing on the field. And keeping track of time remaining in the game.

Aside from a smattering of applause here and there, the parents were completely silent. And myself, as the coach, instead of standing on the sidelines and giving instruction periodically to players, I was sitting on the bench watching quietly, with a clipboard updating positions where the kids were playing on the field. And keeping track of time remaining in the game.  The dense fog wasn’t bothering me at all. Once we were twenty minutes into our ferry ride on the Laura B to the mainland from Monhegan Island, 14 miles off the coast of Maine, even my wife had started to relax. There wasn’t much to see out the window of our 65 foot ferry boat so I had disappeared into reading Carl Hiasson’s latest hilarious novel. I had just laughed out loud at something in chapter eight when suddenly the engines stopped, and seconds later we hit the rocks, shuddering the entire vessel.

The dense fog wasn’t bothering me at all. Once we were twenty minutes into our ferry ride on the Laura B to the mainland from Monhegan Island, 14 miles off the coast of Maine, even my wife had started to relax. There wasn’t much to see out the window of our 65 foot ferry boat so I had disappeared into reading Carl Hiasson’s latest hilarious novel. I had just laughed out loud at something in chapter eight when suddenly the engines stopped, and seconds later we hit the rocks, shuddering the entire vessel. It never really occured to me. It didn’t occur to my wife. Candy never thought of it either. The morning when Annie and I got in the car, it did cross my mind, but only briefly enough to send a quick text to Candy asking, “Do you think it’s OK if I bring Annie?” It never seemed such a concern that I should call in advance or question it. Although alas, that decision changed the day.

It never really occured to me. It didn’t occur to my wife. Candy never thought of it either. The morning when Annie and I got in the car, it did cross my mind, but only briefly enough to send a quick text to Candy asking, “Do you think it’s OK if I bring Annie?” It never seemed such a concern that I should call in advance or question it. Although alas, that decision changed the day.

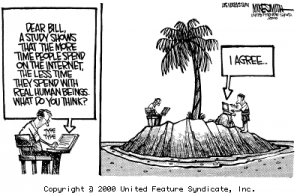

I met a guy named Marcus who was based in Germany and ran an IT services group, which was based in Silicon Valley. Several times a year Marcus would fly to California to spend time with his team, chatting, having meals, talking about work, but also interacting on a human and personal level. He calls these trips “The Flying Handshake.”

I met a guy named Marcus who was based in Germany and ran an IT services group, which was based in Silicon Valley. Several times a year Marcus would fly to California to spend time with his team, chatting, having meals, talking about work, but also interacting on a human and personal level. He calls these trips “The Flying Handshake.” Recently Annie (then 6, now 7) and I were at the store picking out a card to for her to send to a friend. In the card display was a big section dedicated to Taylor Swift. We examined each card – Taylor Swift looking dreamy, sassy, alluring, or even defiant. Taylor can certainly strike a pose. I asked Annie to pick one.

Recently Annie (then 6, now 7) and I were at the store picking out a card to for her to send to a friend. In the card display was a big section dedicated to Taylor Swift. We examined each card – Taylor Swift looking dreamy, sassy, alluring, or even defiant. Taylor can certainly strike a pose. I asked Annie to pick one. Next time you’re standing at the gate waiting to get on a flight and the crew shows up, watch how they interact with each other. It will tell you a lot about how effective as a team they are going to be up in the sky shortly.

Next time you’re standing at the gate waiting to get on a flight and the crew shows up, watch how they interact with each other. It will tell you a lot about how effective as a team they are going to be up in the sky shortly.