It’s not about who, but how you do it

I don’t believe in failure. It is not failure if you enjoyed the process.”

– Oprah Winfrey

Drummer Hoff was one of my favorite childhood books. It’s a story about people who, in turn, provide pieces of a cannon (“Sergeant Chowder brought the powder, Corporal Farrell brought the barrel…”), and then finally it’s Drummer Hoff who fires it off – KAH-BAH-BLOOM! It’s a lesson in teamwork, a lesson in process.

In 1985 Michael Jordan was Rookie of the Year. Yet after just a couple of seasons, critics were whispering if he really had what it takes to bring the Chicago Bulls to championship level. Then Jordan learned to play defense as well as he could score. Then he honed his team instincts, and then came the 1990-1991 season which started an eight year run in which Jordan would lead the Bulls to six Championships. Even the great Jordan couldn’t do it alone.

I recently participated in a 4-hour client presentation with five of my colleagues, all from different parts of the company. It worked beautifully, and we all agreed that each person had played a unique and crucial role. We started by envisioning the outcome. Then, we created a process for composing and delivering the presentation to fulfill that ambition. Finally, we chose the right people to play each position. We didn’t start with the people.

The how is the process. The who are the people who perform the tasks. Yes, the impact, the why, matters. But after settling on the why, think about the how.

Here’s a few reasons why how beats who:

- Process is replicable and scalable. When the process isn’t clearly identified, evaluated, and constantly improved, the results aren’t easily repeatable. When we place results alone as the overarching goal, we de-emphasize the process that got us there.When we de-emphasize the process, we can’t easily retrace our steps and examine, dissect, and replicate how we got there.

- Process emphasizes networks, not heroes. A results-only culture can provide too much focus and reward on sole contributors, creating superstars deemed irreplaceable. Results then can take on a heroic quality. This has a doubly negative effect because it not only relies on the elusive and unqualified “talent” of an individual, but also handicaps that individual with a superstar label.

- Process builds integrity. If it’s the results that count, not how we got there, then we risk inviting unethical behavior to gain the result. The global financial crisis taught us that predatory lending bankers with little oversight and with quick money as their sole motivation were gleefully willing to game the system to their benefit.

- Process cultures remove blame and heighten intelligent risk. Results are the culmination of a series of decisions that are sometimes intricate and often involve many stakeholders. Individuals at all levels of the process chain contribute decisions that eventually lead to an outcome. It’s possible that a strong, high-quality decision can lead to a poor outcome for reasons entirely beyond the control of the person who made the decision.

In 1968 Dick Fosbury astonished the world at the Mexico City Olympic Games by clearing 7′ 4″ 1/4 inches in the high jump. His efforts before 80,000 people were an aberration – an anomaly in track and field events. Dick was a gangly 6’3″ athlete who hadn’t excelled at any event in track and field at his Medford, OR high school and he unveiled a maneuver to set a world record. More remarkably, his competitors failed to recognize and adopt his innovative style and lost – not only on that occasion, but for years to come because they couldn’t acknowledge the power of his innovation.

In 1968 Dick Fosbury astonished the world at the Mexico City Olympic Games by clearing 7′ 4″ 1/4 inches in the high jump. His efforts before 80,000 people were an aberration – an anomaly in track and field events. Dick was a gangly 6’3″ athlete who hadn’t excelled at any event in track and field at his Medford, OR high school and he unveiled a maneuver to set a world record. More remarkably, his competitors failed to recognize and adopt his innovative style and lost – not only on that occasion, but for years to come because they couldn’t acknowledge the power of his innovation.

Woodshedding is an old jazz expression – it means to go deep in isolation to build your chops, get your groove on, master your instrument. As the legend goes, in 1937, when he was only 17 years old, young Charlie Parker – before he became the great “Bird” Parker – would go down to the High Hat Club, also known as “the cutting room” to play with the great session musicians of the day.

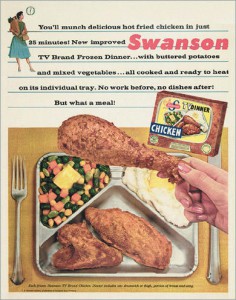

Woodshedding is an old jazz expression – it means to go deep in isolation to build your chops, get your groove on, master your instrument. As the legend goes, in 1937, when he was only 17 years old, young Charlie Parker – before he became the great “Bird” Parker – would go down to the High Hat Club, also known as “the cutting room” to play with the great session musicians of the day. In late 1953 the Swanson brothers had a glut of turkey. Swanson were turkey wholesalers and had overestimated the market. They thought they would make a killing that year on Christmas turkeys sales. Not so much. So now they had 235 metric tons of turkey riding around the U.S. in refrigerated rail cars and the executive team was wondering what to do. Meanwhile the CFO is showing charts of what it cost to have all those turkeys rolling around on refrigerated rail cars per day.

In late 1953 the Swanson brothers had a glut of turkey. Swanson were turkey wholesalers and had overestimated the market. They thought they would make a killing that year on Christmas turkeys sales. Not so much. So now they had 235 metric tons of turkey riding around the U.S. in refrigerated rail cars and the executive team was wondering what to do. Meanwhile the CFO is showing charts of what it cost to have all those turkeys rolling around on refrigerated rail cars per day. Think big! Blue sky! Anything is possible! Let’s build the next iPhone. Or better, let’s disrupt our own business model with a seismic market change, like iTunes. No…wait, like Spotify!

Think big! Blue sky! Anything is possible! Let’s build the next iPhone. Or better, let’s disrupt our own business model with a seismic market change, like iTunes. No…wait, like Spotify! Our twelve year old son walked into the lunchroom at Sugarloaf ski resort a couple weeks ago and said quietly, “I learned how to do a 360.”

Our twelve year old son walked into the lunchroom at Sugarloaf ski resort a couple weeks ago and said quietly, “I learned how to do a 360.”