You’re Trying to Hire the Wrong People

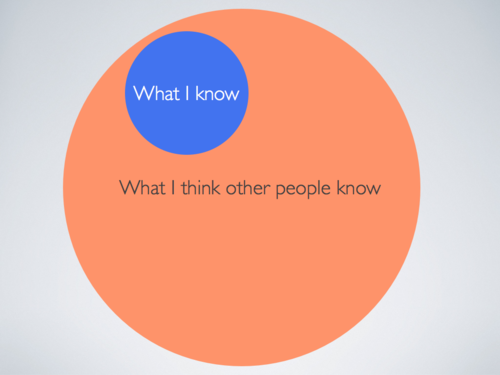

What do you think is the average age of the founders of most new companies? Or an even better question is, what do you think the average age is of founders of high-growth startups? The kind of start-ups that take off and scale and grow quickly? Do you think it’s 25 years old, 35, 45, 55?

When asked this question most people say 25 and the voting gets lower as the age range goes up. The truth is that the average age of all new founders is 42, but the average age of the founders of the fastest growing and most lasting successful companies is 47. And founders with an average age of 50 are almost twice as likely to create a fast growth firm with a highly profitable exit, the kind of exit that makes investors rich.

Surprised? Maybe you bought into the romantic idea that all savvy entrepreneurs are young like Steve Jobs, or Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerberg or Sarah Blakely, the founder of SPANXX. The truth is that older entrepreneurs have more experience, broader networks, and deeper wisdom, which seems to contribute to their capability to innovate successfully. And by “innovate successfully” I don’t mean they possess creativity. Lots of people are creative, but the difference between being creative and being innovative is the ability to execute – to lead a team to realize a shared vision.

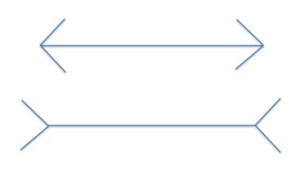

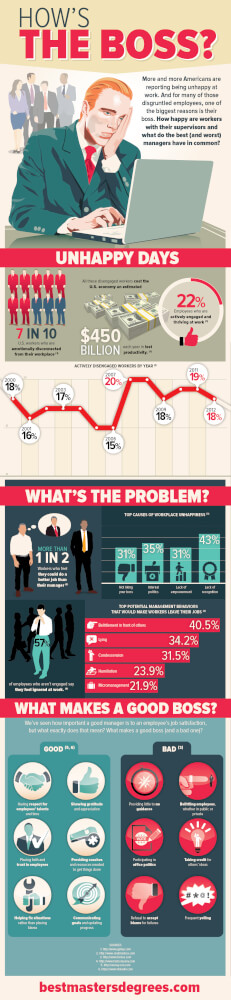

As more and more work is routinized, outsourced, or automated, highly innovative people are exactly the kind of people most organizations need and want right now, but instead most hiring managers are hiring for PLUs – People Like Us. To ensure we have “culture fit” we hire people who look, act and behave like we do. We know we should be hiring for values, but often we confuse values for people who have the same interests.

That cultural conformity is terrible for innovation. Serial innovators are people who have lots of diverse interests, zig zag from job to job, often hold different kinds of roles within companies, experiment in different domains, read widely, experiment with hobbies, and often stay in contact with people who work in different lines of work. They are also often consistently counter-cultural in their efforts. Chuck House, who developed a number of innovative new products for Hewlett-Packard, was awarded a “Medal of Defiance” by the President of HP.

And because of this diversity and breadth of experience, these candidates appear on paper to be inconsistent in their work. On paper they look flakey, distracted. But they are also exactly the kinds of people who are more likely to borrow brilliance from other domains because of their experience, and become powerful innovators for your company.

Most job descriptions are overly narrow, and hiring managers focus on resumes that have predictable, consistent trajectories that align with the target abilities they are trying to hire for. Keep in mind this is a short-sighted approach. It’s a tactical hire, not a strategic one. When hiring, don’t just think about the task you are trying to accomplish, think about the kind of company you aspire to build.

Finally, make sure you have a diverse set of interviewers. Women are more likely to join a company when they can interact with women who are already there, and can witness a company’s commitment to diversity. As Katherine Swings points out, one of the biggest deciding factors on whether or not a female candidate accepts a job is if there was a woman on the interview panel.

Innovation isn’t rocket science. It can be deconstructed and learned by anyone. Try our course Out•Innovate the Competition to build measurable innovation in your workplace.

- ____________________________________________________

Last summer, my son and I bicycled across America with two other dads and their teenagers. We published a new book about it called Chasing Dawn. I co-authored the book with my cycling companion, the artist, photographer, and wonderful human jon holloway. Buy a copy. I’ll sign it and send it to your doorstep.

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of

Shawn Hunter is President and Founder of